Steve Whitaker, Features Writer

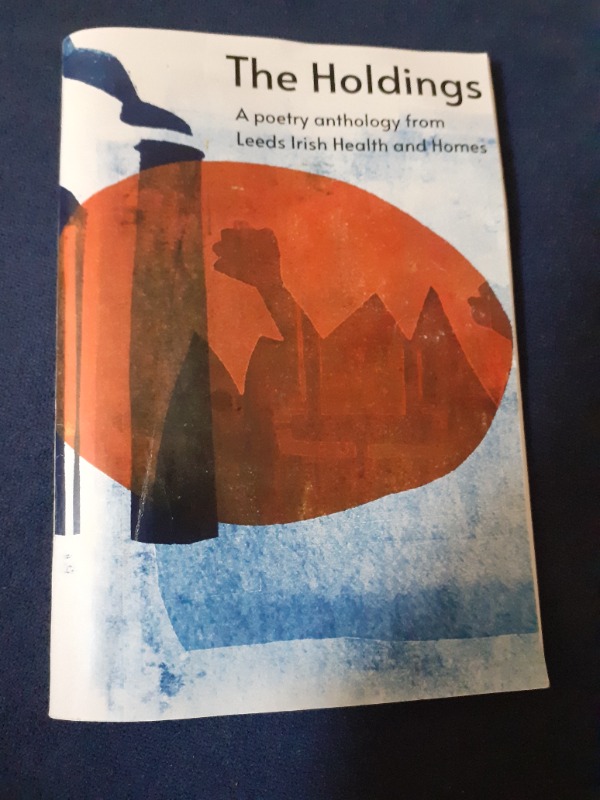

The Seed In The City: The Holdings – A Poetry Anthology From Leeds Irish Health And Homes

The poems are, by turns, candid, open and emotionally charged, and if the process of exposure sometimes rides roughshod over formal considerations, then the clear investment of heart renders any sense of propriety meaningless. For the artifacts – among other items, a nineteenth century Irish rioter’s cosh and a silk Orange Order sash – are totemic to the beholder(s), signifiers of wider cultural grievances; metonyms, in the subsequent poems, for memories, and catalysts for kaleidoscopic bursts of inherited association. For Alison Bohan, an access of filial emotion precipitates a wider ancestral reckoning whose contemplation is a source of both immense pride and sorrow; from the sites of ancient battles to the fever hospitals of Dublin, heartsore fealty connects the exiled narrator to a sense of home in the caoineadh, and in so doing, effects a transformative, Achillean solemnity in the poet:

‘Cú Chulainn speared Ferdia

Took his foster brother’s life.

Embraced him,

Then wept.’ (‘Driving With Dada’)

And if Nicola Carr’s keening – at once for love and for the passing of the dead through longevity or by malign intention – is ameliorated by the consolatory omnipresence of a redemptive God (‘That Day’, especially), then Mary Clark’s first-hand experience of the jaundiced attitude of those who reinforce the moral stranglehold of catholicism in the interests of retribution, is less forgiving. Approaching the church from a different angle, the talisman of Clark’s memory is pierced, particularly, by the sharpness of the Irish cultural tongue whose quickness to disown was tantamount to ostracism. Clark’s single-parent divorce, encouraging opprobrium not least amongst the clergy – ‘If people knew I was a friend of yours!’ – is infused with the kind of irony that is properly measured in exile. The province of shadows about to be exhumed in Tuam haunts the testimony of the indoctrinated and the institutionalised, and gives leverage to Clark’s retrospective decision to move on:

‘But consider more strongly,

Fewer secrets: less harm.’ (‘Family Secrets’)

The access of memory that yields, in Bronagh Daly, a return to the language of the old country, is soaked in its associative power, and gives on to an historical topography that is ripe with sibilance in the wounds of the generations:

‘Famine-stained farmland,

Scars still visible on these hills

And blood-soaked memories

Of bomb scares and snipers stood still:’ (‘The Land of My Youth’)

It is fitting that Daly should find a kind of peace in the idea of connection and growth. If her home in Leeds will never consume the homesickness ‘For Tir na nÓg, the land of my youth’, it remains a repository of hope as the seeds of future generations thrive and flourish. (‘The Seed in the City’)

Ian Duhig

‘Valkyries sang Clontarf’s wrong victors,

wove flesh clothes for ghostly emperors.

Poems can be noisy looms spinning lines:

mill-girl signs to you, over this one’s din.’

Keith Fenton picks up the plangent tones of abuse, neglect and xenophobic indifference in the aether of memory, whether recalling the feisty resilience of his mother, whose eyes were ‘Celtic emeralds’ twinkling ‘like a tyrant’s / Kryptonite’, or the double-handed, cultural imperialism of the English who willingly accepted the help of the Irish in defeating the Germans but resolutely refused to offer courtesy in kind:

‘You can stoke the fires,

roast in your iron vault, but

you cannot stay in this boarding-house, Paddy.’ (‘You’re Allowed in the Engine Room and Nowhere Else, 1916’)

Diving deep into the ‘protected’ well of memories, Natalie Hughes-Crean finds a kind of salvation in elegy as celebration, in a rather beautiful study of a marine engineer uncle, whose regular overseas absences make of his persona a Proustian madeleine. Here, a tin of swarfega, and the Latin phrasing that somehow transforms the act of its application into one of quiet family solemnity, is rendered almost as a sacrament, the red gel becoming the olive oil and fragrant balsam of chrism:

‘We rub it in to loosen dirt, hand over hand, paying attention to nails,

palms, each other, the ceremony of the task still remembered: ‘Lavabo’. (‘Lessons in Latin and Life’)

The co-editor of this fine collection, Laura McDonagh, takes a measured and closely-observed look much deeper in time to trace ancestry in the Iron Age bogs of Tipperary and Meath. In three sestets of real figurative vigour – ‘skin like / soiled serrano ham, paper-thin’; ‘a bronze bust melting / to a Dali clock’ – the poet finds a haunting likeness, most presciently, in the hands of the long dead, whose fingers wear labour as we wear labour, a sign of connectedness, of foreshadowing:

‘But it’s the hands,

able to grip a pig, coax an ass,

build a wall, weave thatch from grass,

fingers gripping an invisible shank’. (‘What We Find in the Earth’)

John McGoldrick’s ‘muse’, an Irish Elk skeleton submerged in Lough Gur, is the starting point for a barbed meditation on the theme, not of connection, but rather of division and state-mandated neglect. ‘Fia Mór na mbeann’, a literate and sardonic dismantling of political indifference, as a swamp is dredged of bones for the making of manure to till the fields of England, is set in 1847, during the Famine. In ironic juxtaposition, McGoldrick skewers those in the ‘Mothering parliament’ who ‘absently’ docketed millions of animals for export whilst the indigenous populations starved. The poet’s final quatrain is a triumph of harrowed concision in a poem of necessary detachment, its final line empty of hope:

‘On the still drying shore of Knockadoon

At Áine’s passage stone

Spailpíns rest their picks

Dreaming of pike darkening the reeds’.

And if the warp and weft of Treasa Ní Drisceoil’s remembrance of things past casts a charmed spell over her present, then the reader is equally enchanted by the sensory and rhythmical beauty of her short, but interconnected series of poems. Ingathering memories in a joyous synaesthesic compendium, her clear sense of affection for her former home in Co Cork reminds of the lyrical tenderness of Laurie Lee’s re-envisioning of the Cotswolds. ‘The Fates’ are rendered the more powerful because the poet is self-consciously cognizant of the inherence of distortion to all nostalgic contemplation, and to the latter’s propensity for release:

‘Long long days and longer nights weave and spin weave and spin

An embroidered and embellished thing my memories

metamorphosed into wings.’ (‘Spinning and Weaving’)

And it is well that Carol Wright’s questing poem-as-research, ‘Thomas McCall’, should conclude an anthology that is, by turns, searching and heartfelt, ravelled and unravelled. Seeking the elusive figure of Thomas from the thinnest of suggestions – ‘born Ireland 1824’ – Wright takes the reader on an engaging journey around the industrial hinterlands of England in pursuit of her peripatetic land surveyor great great great grandfather, and by way of his own, dimly-lit ancestry. At once tantalisingly within reach, then adrift in a dark genealogical abyss, Thomas McCall (McCale, MacCathail?) is an evanescent reminder that ancestry, like indigenous language, sustains only so long as we strive to keep its name alive:

‘I call / yours for my roll. / Just who are you Thomas McCall?’.

To buy a copy: info@lihh.org

‘