Paul Spalding-Mulcock, Features Writer

'How Do You Embrace A Paradox? You Let It Go!' : The Book Of Niall By Barry Jones

Known for their comically dark performative style, the duo have forged a heterogenous oeuvre predicated upon acting out scenes in character...

The reader as copacetic creative partner, both forms and judges the verisimilitude of the make-believe reality being presented by an author, paradoxically knowing that the very words they are reading are false cyphers, artificed semiotic signposts contriving to be the very things they describe, or connote. In essence, when we enter into a book’s false reality, we do so suspending our cynical disbelief to a degree - we don’t want to doubt too much, as doing so renders the act of reading unsettlingly futile and largely inert. The same could be said of our engagement with life itself, a belief extensively promulgated by John Paul Sartre and a bedrock tenet of Existentialism.

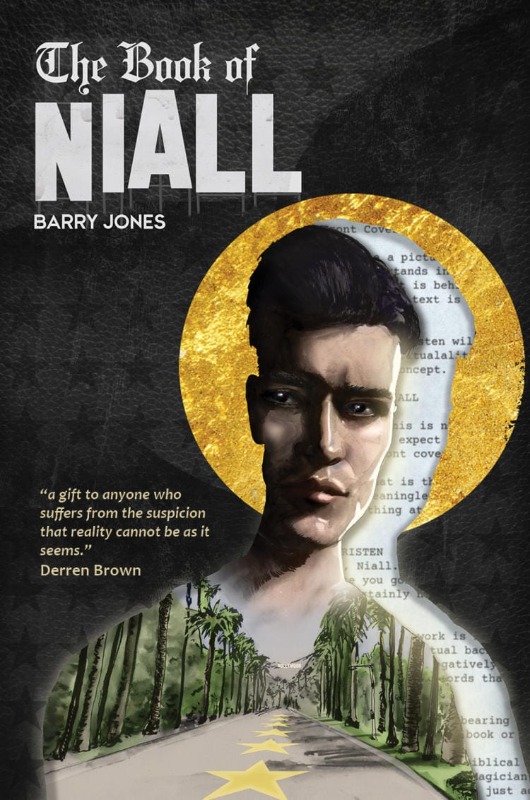

So, what happens when a professional, world-renowned magician with a reputation for exploring the ubiquitous nature of illusion and its haunting of our logocentric psyches, makes his literary debut with undeniable éclat, in the form of a graphic novel? The answer is, The Book of Niall.

Jones is one half of the Scottish Bafta-nominated magical act, Barry and Stuart. Known for their comically dark performative style, the duo have forged a heterogenous oeuvre predicated upon acting out scenes in character, whilst shocking their enraptured audiences with feats of illogical illusion. In short, they offer the audience a fake reality whilst concealing the demarcation point between fact, and fiction.

Their first TV show, Magic, signalled the pair’s fecund imaginations and heralded future success, garnering a nomination for Best Comedy Series at the Rose d’Or International Television Awards in Montreux in 2004. Subsequent TV shows and festival appearances have gained further accolades, solidifying their status as highly inventive magicians, sardonically exploring a cornucopia of knotty themes, from the paranormal to the nature of reality itself.

A typical aspect of the condition is staring at the mirror, and considering the reflection of oneself to be a stranger

Prior to making the decision to write his book, Jones had spent the previous two decades persuading people to doubt what they saw. However, haunting his own troubled psyche was the ineffable sensation that his own sense of reality was no more real than the illusory world he presented to his gulled audiences. This sense of derealisation was both overwhelming, and the imperative catalyst behind his decision to write a graphic novel focusing upon his phantasmagorical demons, and dislocated sense of self. Jones’s search for the therapeutic catharsis of understanding his own condition led him to become fascinated by the profoundly paradoxical ontological enigmas at the heart of metaphysics, the philosophy of identity and of language itself. Seemingly crippled by the logocentric paradigms scaffolding Western cultural understanding, he appears to me to have found himself teetering on the brink of nihilism, and perhaps losing any sense of his own identity. It turns out that such ‘a dark night of the soul’ is not uncommon.

Jones suffers from two specific conditions: Depersonalisation and Derealisation, both considered to be as common as schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neither condition is widely acknowledged, difficult to express and clinical diagnosis is fraught with complexity. Broadly, Depersonalisation, (DP), causes a person to feel that they do not exist and that they have become avatorial characters in a narrative not of their making. A typical aspect of the condition is staring at the mirror, and considering the reflection of oneself to be a stranger.

Derealisation, (DR), shares much in common with its sister condition, with the key difference being that clinical symptoms refer to the external world, rather than the individual’s experience. Sufferers report feeling as though reality is a movie set, with everything perceived seemingly pre-destined and artificially contrived. This leads to a debilitating loss of personal agency, constant episodes of déjà vu and even language deliquesces into meaningless symbols devoid of substantial relevance.

Both conditions can exist simultaneously and can be chiefly catalysed by stress, anxiety, alcohol, or fatigue. Some eminent physicians believe that over half of all adults will suffer from either, or both invidious maladies during their lifetimes. Currently, there is no certified cure.

The Book of Niall is Jones’s sublimely creative attempt to both portray, and understand both DP and DR, and therefore himself. The choice of Graphic Novel as the medium for this exploration is an apposite and profoundly imaginative response to Jones’s creative dilemma - how does one convey the inexpressible, voice the ineffable, or meaningfully address a topic with a miasmic, intangible form recalcitrantly resisting explanation ? As conflicts go, this artistic puzzle appears to be ostensibly irresolvable !

The term ‘Graphic Novel’ was originally coined by Richard Kyle in 1954, with Will Eisner’s A Contract With God published in 1978, one of the earliest works to use the term in its branding. Before Kyle’s label had been conceived, the form had long since existed, with perhaps the oldest example being The Adventures of Mr Obadiah Oldbuck, published in 1837 by the Swiss caricaturist Rodolphe Topffler.

The putative origin of the American graphic novel is traditionally acknowledged to be Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s, Doctor Strange. However, as predominantly serialised episodes, aficionados of the genre cite Blackmark, a sci-fi tale by Gil Kane and Archie Goodwin as the first American work to truly reflect our modern concept of Graphic Novels, illustrated stories employing ecphrasis to deal with intellectually complex, or substantial themes explored with a cerebral adult audience in mind. Frank Miller’s Batman : The Dark Night Returns, and Alan Moore’s Watchmen evince this artistic principle, with Art Spiegelman’s two-volume, Maus winning a Pulitzer Prize.

The Book of Niall introduces us to its chief protagonist, successful Hollywood actor Niall Adams. Within a few pages, the reader is rapidly and inexorably drawn into the psychological wormhole threatening to rob Niall of his sense of self, and shatter his tenuous grip on reality. What follows is an interactive, fabulously immersive journey through Niall’s fractured psyche as he wrestles with life’s thorniest epistemic conundrums, knottiest philosophical topics, and the oppressive forces of nihilistic numbness. En passant to the brilliantly conceived denouement, Jones explores Descartes, Sartre and those who have architected our prevailing ontological conceptions.

In addition to a narrative script artfully empowering the reader as both witness and co-creator, Jones laces his kaleidoscopic odyssey with pictorial illusions, deftly finessed word games and a plethora of perfectly executed magical mind games. The reader is simultaneously discombobulated and enlightened as Jones masterfully orchestrates our journey to understanding and empathy.

In wrapping his tale up in both words and pictures, Jones has enabled the osmotic transfer of meaning to defy the limitations of either medium in isolation. Woolf’s ‘cathedral of the mind’ rises from the paradoxical chaos before us, and its vaulted columns resolve into magical focus.

Reading The Book of Niall is a scintillating feast for the senses, unlikely to leave any reader anything other than deeply satisfied, on many levels. The artwork, drawn entirely by the author, is breathtakingly emotive, distressingly hypnotic, and perfectly matched with the pitch-perfect prose accompanying it. For me, Jones has seized upon the visceral and cerebral power of the graphic novel form to fully realise its artistic, and intellectual potency.

I will take a leaf from Jones’s book and break with convention by concluding with another reviewer’s thoughts on this groundbreaking, artistically innovative gem - those of David Kyle Johnson, Ph.D and Professor of Philosophy at King’s College: ‘An enthralling exploration of critical issues, both philosophical and psychological. It is refreshing, challenging, beautiful and unique. I recommend it especially to those who seek out art that does philosophy. It is not, after all, just a comic book’.

First Published in the UK in 2022 by the author.

Represented by @kenyon_isabelle