Steve Whitaker, Literary Editor

Review: A History Of Pictures - From The Cave To The Computer Screen By David Hockney & Martin Gayford

Which is not to demean either the intellectual or aesthetic content of the book. Gayford’s encyclopaedic knowledge of the history of art reinforces Hockney’s insightful impressionism. Framed in the form of a conversation transcription, the two take turns to narrate us through the chronology of a long history, whilst cross-hatching conventional wisdom with a modern, profoundly perceptive take on the past. The lasting impression the unpractised mind takes away – and the book does not reek of patrician elitism – is that of a continuum of light: Hockney believes less in the evolution of art over time than individual focus honed to unnatural strength in every era. There were developments, sure, but differences in artistic perspective may have had more to do with the way the artist perceived his subject than any inability to recreate an extra plane; for Hockney, a new dimension may not have been necessary at any particular point in time. But, and as Gayford notes, a ‘personal angle on reality’, good or bad, crude or even, is afforded us from the recesses of time.

Caravaggio, 'The Calling of Saint Matthew', 1599–1600. Oil on canvas. Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Sometimes covering ground he has explored before – Hockney remains as keen as ever to insinuate primitive optical machinery into the re-creation of perceived verisimilitude in the artistry of the Renaissance, not least in the case of Caravaggio, and later of Vermeer. It was fortuitous for Johannes Vermeer that the fabulously high-quality lenses which were pushing the boundaries of seventeenth-century astronomy were being manufactured literally streets away from his Delft home. Using such pristine lenses to reflect back images of tableaux external to where the glass was applied, the Flemish Master was able to represent likeness of colour and architectural perspective with extreme accuracy, as though a modern colour photograph had recreated the Delft of the 1650s. Where, in the depiction of what Gayford insightfully calls ‘optical drama’, Caravaggio traced shadow and perspective with the help of the new medium, Vermeer and his contemporaries found light and depth in detail.

Jan Vermeer, View of Houses in Delft, known as 'The Little Street', c. 1658. Oil on canvas. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

This, on the whole chronologically linear, journey through pictorial time is not restrained by conventional ways of seeing; often Gayford and Hockney illustrate a likeness of stylistic approach by recourse to the work of a much more recent artist or photographer. Picasso’s primitivism, for example, underlines an affinity with the most ancient of cave pictures, as it also describes a continuity of creativity. Or, as in the unexpected vignette of a Rembrandt sketch, the genius of artistic suggestion is illuminated in the wider artistic context of the making of simple marks on media as diverse as stone, paper and silk.

Eugène Durieu, 'Female Nude', 1854. Calotype. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

‘Sensing the powerful triangle made by the crouching father, who has excited eyes that are two beautiful ink blobs, one realizes the quite complex space the figures make. But then, there’s a passing milkmaid, perhaps glancing at a very common scene, and we know the milk pail is full. You can sense the weight. Rembrandt perfectly and economically indicates this with – what? Six marks, the ones indicating her outstretched arm. Very few people could get near this.’

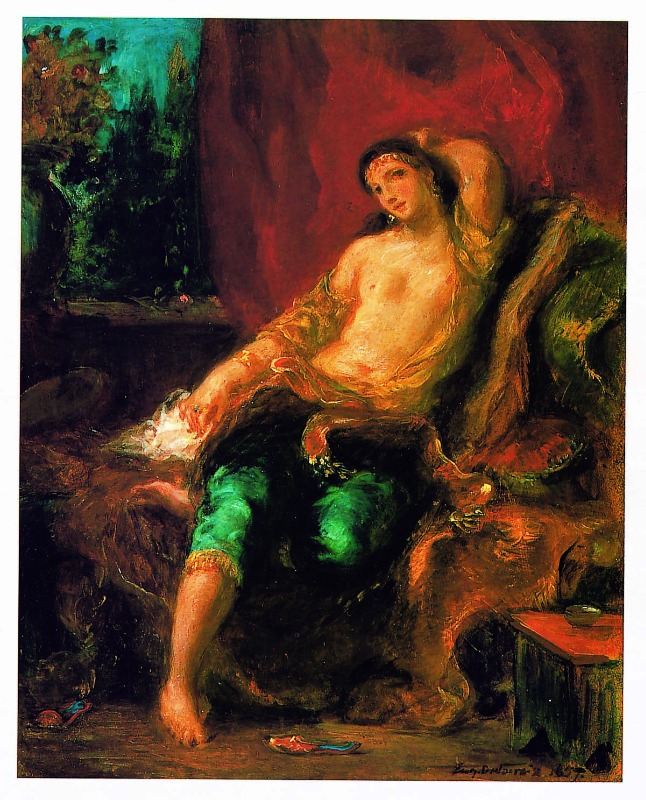

Eugène Delacroix, 'Odalisque',1857. Oil on wood. Private collection

The limitations of the photograph to envision reality is a crux point of Gayford and Hockney’s comprehensive analysis: excepting where photographer as artist painstakingly follows an, in equal parts, aesthetic and forensic process of observation and superb technical skill – Julia Margaret Cameron and Nadar’s portraits are exemplars – the book is clear on the power of art to add weight, gravitas and depth to received impression. The distinction is perfectly illustrated by the fine nude study of 1854 by Eugène Durieu, whose attempts to capture a relaxed female form is given seductive allure in the rich colour contrasts and sensuous folds of Delacroix’s ‘Odalisque’. Modelled directly on Durieu’s calotype, ‘Odalisque’ is far removed from its inspiration; ‘it would be hard’, as Gayford says, ‘to guess that Delacroix had used a photograph at all’.

That we return to where we started is no more than a coincidence. David Hockney sees no reason to assume that art is bound on a trajectory of inevitable progress and development. ‘Why’, he asks, ‘does it have to go anywhere? Art hasn’t ended, and neither has the history of pictures’.

A History of Pictures: From the Cave to the Computer Screen is published by Thames & Hudson.