Steve Whitaker, Literary Editor

Poem Of The Week: 'London' By William Blake

William Blake

London

I wander thro' each charter'd street,

Near where the charter'd Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg'd manacles I hear

How the Chimney-sweepers cry

Every blackning Church appalls,

And the hapless Soldiers sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls.

But most thro' midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlots curse

Blasts the new-born Infants tear

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.

I wander thro' each charter'd street,

Near where the charter'd Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg'd manacles I hear

How the Chimney-sweepers cry

Every blackning Church appalls,

And the hapless Soldiers sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls.

But most thro' midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlots curse

Blasts the new-born Infants tear

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.

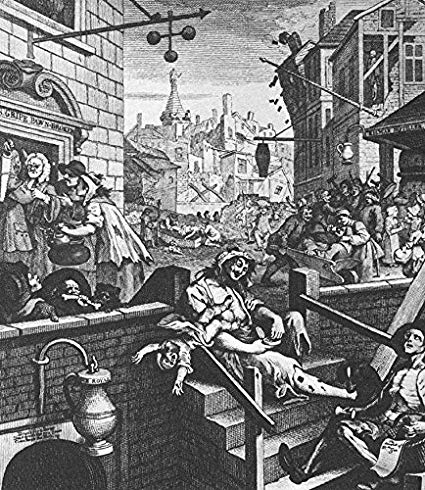

'Gin Lane' by William Hogarth

Tyrannised by brute circumstances, by a body politic whose economic agenda sacrifices reflection to profit, and by a Church whose strategic secular interests maintain the corrupt fabric at the expense of true spirituality and social concern, Blake ‘charters’ the progress of the state as though by business contract. The imposition, and self-imposition, of ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ give crushing alliterative weight to the howls of pain which will ensue.

The raw power of Blake’s declamatory plea in the second stanza is the mark of an anger which will find no restitution, save in imagination. The bitter rendering of the marriage ‘contract’ in the poem’s concluding line utterly undermines the institution’s claim to sanctity. One of the most perfectly judged oxymorons in English literary history, we are obliged to believe that the ‘Marriage hearse’ spells another kind of incarceration and entombment, a further reinforcement of constraining social mores whose ‘chartering’ compromises any sense of sincere spiritual vigour.